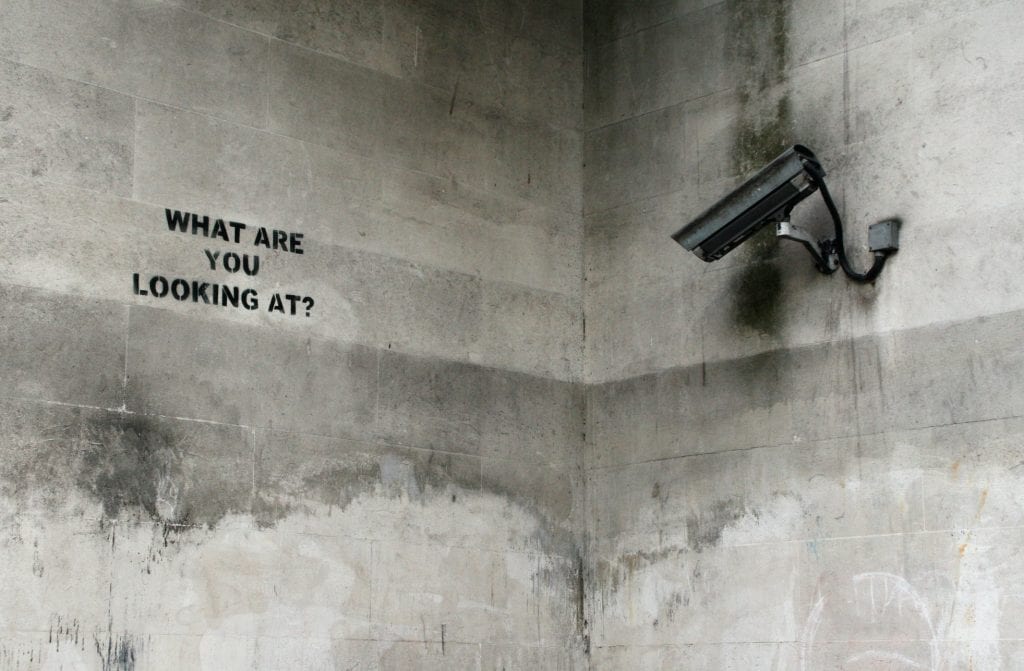

Britain’s most famous – and enigmatic – graffiti artist Banksy once proclaimed that “copyright is for losers.” Now, having lost a two-year legal fight over the trademark rights of one of his iconic artworks, that claim has come back to haunt him. On September 16, the European Union Trademark Office (“EUTM”) invalidated a trademark registered by Pest Control, the official body that authenticates Banksy’s art. The trademark consisted of Banksy’s iconic mural Flower Thrower, originally painted in the Palestinian town of Bethlehem.

This legal dispute initially erupted between Pest Control and British greeting card company Full Colour Black, which often uses artworks by Banksy. In March 2019, Full Colour initiated proceedings with the EUTM, in which it sought for the Flower Thrower mark to be cancelled, claiming that it was filed in bad faith.

The row hit the headlines after Banksy opened a store – entitled, Gross Domestic Product – in South London in the fall of 2019. At the time that his outpost opened, the mysterious artist spoke to the budding trademark battle, saying, “A greetings card company is contesting the trademark I hold to my art and attempting to take custody of my name so they can sell their fake Banksy merchandise legally.”

Banksy also revealed that he had been legally advised that the best way to remedy the situation was to create his own merchandise in order to show that he was actually using his trademark in commerce, as required by law. Up until that point, the famously secretive artist had never regularly manufactured or sold merchandise bearing any of his own branding. But such statements – not unexpectedly – backfired. The EUTM noted in its decision that in opening a shop specifically to sell merchandise showing the Flower Thrower (i.e., the artwork that Full Colour Black wanted to use and the trademark registration, it wanted to invalidate ), Banksy had admitted that his use made of the Flower Thrower mark on merch was not genuine use.

Instead, the newly-introduced merch that Banksy was offering up by way of his Gross Domestic Product shop was being done in bad faith, inconsistent with honest practices and aimed at creating or keeping a share of the market by selling products simply to circumvent the law. This is not just bad news for the Flower Thrower mark. The decision could also damage other Banksy trademark registrations that incorporate his various iconic artworks, which are now at risk of being invalidated on the same grounds.

Trademark or copyright?

The case raises other issues, too. For one thing, it poses the question of whether artworks be monopolized by registering them as trademarks? Copyright and trademarks are different intellectual property rights. While copyright aims to protect artistic works, such as paintings, trademarks protect logos and signs that help consumers to distinguish between the products/services of different companies and to make informed purchasing choices. The latter is at issue here, as Banksy – who has made clear his dislike of copyright – has tried to rely here on trademark law to protect his artworks. And this is not the first time he has done so.

The reason Banksy does not point to copyright law, and instead relies on trademarks? A copyright suit would require Pest Control to show that it has acquired the copyright from the artist. This would reveal Banksy’s real name, which the famously anonymous artist wants to avoid, as it would potentially remove his aura of mystery and affect the commercial value of his art.

Also, copyright is limited in the duration of its protections, while trademarks can be continuously renewed; trademark rights in an artwork – presuming that work functions as a trademark – can give the artist a perpetual monopoly over it. This may offend a basic intellectual property law principle, namely that after a specific period of time everyone should be able to use, and build upon, artworks that have fallen into the public domain.

Banksy is not alone in looking to trademark law to protect his works. Of course, there are artworks which are registered and enforced as trademarks, such as Disney’s iconic characters. However, in most cases the trademark-protected work of art is used in a genuine way, with merchandise regularly produced and sold by the rights holder. But where the use has been token and aimed just at getting around the law, the scenario is arguably a bit different. This is more so in cases like Banksy’s, when an artist does not want to claim copyright, but at the same time seeks potentially perpetual trademark rights over his art.

So, Banksy’s statement – “Copyright is for losers” – has now come back to bite him. His negative opinion about an important intellectual property right clearly jeopardizes his position in proceedings where proprietary rights are debated, as the EUTM suggested in its decision.

Certainly, an anti-establishment viewpoint does not prevent artists from relying on “establishment” legal tools to protect the very rights they criticize. Everyone has the right to freedom of expression and a trademark owner cannot lose the right to register a mark because he has steadfastly opposed copyright law. In other words, you can still be anti-establishment and take legal action to protect your intellectual property. But what you cannot do is behave as Banksy did in creating his shop to simply get around the law and keep perpetual monopolies over his art.

Illegal graffiti

Beyond that, the EUTM noted that illegal graffiti cannot be protected by copyright because it is produced through the commission of a criminal act. It added that as graffiti is normally placed in public places for all to view and photograph, no copyright can be claimed.

But as lawyers and academics have argued for years (including in response to arguments by the likes of Swedish fast fashion giant H&M and Italian fashion brand Moschino), these statements are not accurate. The process of creating an artwork, whether legal or illegal, is not conclusive when it comes to determining whether copyright comes into existence. For example, if I steal a pencil and create a wonderful drawing, why should I be denied copyright and be forced to tolerate someone else cashing in on my work? It would be unfair. The same could be said of illegal street art. Also, the fact that graffiti is placed in public locations does not assume that artists waive or are deprived of the rights copyright law offers them. That is simply mistaken.

Apart from this point, the decision is well-reasoned and fair. If Banksy wants to own, keep and enforce registered trademarks, he needs to act in good faith, and start using them seriously by regularly selling merchandise. He only needs to reveal his name if he wants to pursue copyright actions. Keeping anonymity is more important to Banksy than winning copyright cases.

Enrico Bonadio is a senior lecturer of Intellectual Property Law at the City University of London. (Additional reference to H&M and Moschino cases courtesy of TFL)