The Chinese daigou trade is expected to get a second wind, as “Beijing is planning to keep its pandemic border restrictions in place for at least another year,” the Wall Street Journal reported on Tuesday, noting that a “provisional timeline of the second half of 2022 was set during a meeting of the country’s cabinet and other government bodies” last month. While the “surrogate shopping” practice of daigou – which sees professional shoppers purchase products in other markets, including in duty-free shops in South Korea, Japan and Australia for those on the Mainland, thereby, avoiding import taxes and/or unharmonized prices – experienced a decline leading up to pandemic and amid COVID travel and supply chain upheaval, daigou activity has picked up again since Chinese consumers are limited on the international travel front.

No small matter, daigou is a multi-billion-dollar market, with Re-Hub finding that the value of the parallel import trade – which largely revolves around coveted luxury goods – has grown “exponentially” in recent years, amounting to a market that is worth an estimated $57 billion. In a testament to the might of this market, the tech solutions company analyzed nearly 30,000 product listings on Alibaba’s TaoBao marketplace this February, with a specific focus on five of the most iconic luxury handbags on the Chinese market: Gucci’s Marmont bag, Balenciaga’s Hourglass, Celine’s Box bag, Loewe’s Puzzle, and Prada’s Hobo. It found that daigou sellers generated more than $4.3 million from the sale of almost 4,000 of the aforementioned bags.

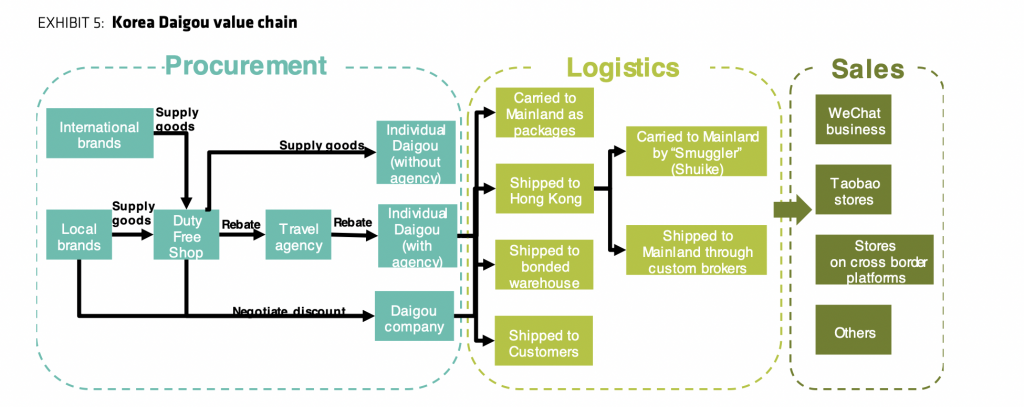

Such robust demand has seen daigou – which Wang Jian, a professor of University of International Business and Economics, says is “a normal business practice based on the inevitable fact that market prices are different in different places” – shift over time from small-scale operations to larger, more sophisticated and professional endeavors, as Chinese consumers clamor to get their hands on luxury goods that commonly range from pricey skincare to handbags without the robust markups, and the Chinese government continues to grapple with losing out on a potentially substantial source of tax revenue.

Increased Activity

The enduring travel and border restrictions in China that were announced this week will almost certainly help spur increased activity again in the daigou industry, as luxury buyers in China are being forced to do much of their shopping at home (as opposed to during international excursions), where an often-significant gap exists between prices of luxury goods compared to when they are sold in markets, such as Italy or France, and in duty-free destinations like Hainan, an island in southern China. As we noted last week, despite a narrowing of the price gap that has come as a result of slashed import-linked taxes by the Chinese government, which is actively looking to repatriate Chinese luxury spending, the playing field when it comes to price is still not even in many cases due, in part, to a lack of price harmonization by brands.

While Bloomberg previously asserted that brands, particularly small ones “that lack the resources to physically set up shop in China” have benefitted from an influx in revenues thanks to daigou sales, Re-Hub says that “it is important for brands to control their brand image and quality assurance” in connection with the daigou trade “by taking proactive steps” since the “vast size of [this] market and the lack of any control” that brands have on pricing and their brand image “can substantially disrupt revenue and branding efforts.” This has left brands to balance the draw of boosted revenues (particularly amid striking COVID sales slumps) with the need to crack down on out-of-channel consumption behaviors for the sake of brand image maintenance, an ongoing issue when it comes to luxury goods purveyors and the grey market in general.

Louis Vuitton is one brand that appears to be taking direct action, with Moodie Davitt revealing early this month that the Paris-based luxury titan is “progressively withdrawing from much of its downtown duty-free business, including its long-standing and expansive Korean presence,” with such action reflecting “some disquiet as to the increasingly daigou-driven nature of those stores.” Meanwhile, other brands, such as Chanel, have taken to harmonizing prices in recent years in furtherance of what the French fashion brand called “a bold [move] initially,” but one that was “in favor of our customers,” and made “purely out of fairness, [as] it was no longer acceptable for us to allow significant price differentials to develop.”

The Future (and Legality) of Daigou

As for what can be expected of the daigou trade following the COVID-related boom, Bernstein suggests that growth of the industry very well may “slow down over time,” with Chinese duty-free consumption in Korea for daigou purposes, for instance, on track to begin falling in 2024, a phenomenon that will coincide with rising duty-free sales in China and larger efforts by the government to keep newly-recaptured Chinese spending at home.

A hot spot worth paying attention in the evolving daigou landscape: Hainan, the alluring island province in southern China, that “is set to grow by 18X fold between 2019FY and 2025,” per Bernstein, and to a noteworthy extent, holds a key to consumption containment in China. One of latest indications of what Bernstein calls the Chinese government’s “endeavor to grow ‘onshore’ Chinese duty-free spending,” and thereby, decrease Chinese daigou purchases in places like Korea? This time last year, Hainan increased its annual tax-free shopping quota from 30,000 yuan ($4,633) to 100,000 yuan ($15,433) per person, expanded the range of duty-free goods from 38 categories to 45, and lifted the previous tax-free limit of 8,000 yuan ($1,235) for a single product.

In terms of the legality of the daigou trade, Gowling WLG’s Ivy Liang, Vivian Desmonts and Jamie Rowlands state that “China’s current laws, regulations and judicial interpretations do not explicitly provide for the regulations of parallel imports,” and as a result, there is “ambiguity” when it comes to the practice, with “each parallel import case requiring a case-by-case analysis.” (For one point of reference, in a trio of cases from May 2020, the Guangzhou Intellectual Property Court allowed for the parallel import of non-luxury goods products on the basis that the products were genuine goods and thus, the unauthorized import and sale did “not violate the principles of good faith and recognized business ethics, and therefore, did not constitute unfair competition.”)

At the same time, Feng Xiaopeng, a partner of King & Wood Mallesons, told Chinese news outlet CGTN that “the regulation on offshore duty-free shopping in Hainan released by General Administration of Customs in July 2020” prohibits the purchase of “duty-free goods for others or resell them in the mainland market with the purpose of making profits.” However, uncertainty is not off the table, as “the actual conditions are much more complicated,” particularly since “it is difficult for regulators to determine the limits of ‘profit-making.'”

Wang Jian echoes such uncertainty, stating that it is difficult to plainly state that price arbitrage and parallel imports, which are at the heart of the daigou trade, are illegal across the board. Instead, he says, daigou is more accurately described as “actually exploiting policy loopholes,” which continues to enable it to thrive.