Last month a noteworthy case came to a close – one that did not exactly involve fashion or luxury goods, but that nonetheless, could have interesting implications for the industry, as it involved Amazon’s ability to sidestep liability for the goods offered up on its sweeping third-party marketplace. In a filing in December, Maglula Ltd. revealed that it settled the lawsuit that it had filed against Amazon in 2019, in which it accused the e-commerce titan of infringement and counterfeiting in connection with the sale of “cheap” counterfeits of Maglula-branded firearm magazine loaders and unloaders on its platform.

In its complaint, Maglula argued that Amazon was offering up and selling counterfeits, as well as products that infringed its copyrights and patents, and that despite its “extensive and repeated requests” over a three-year period, Amazon failed to take reasonable steps to prevent or remedy the infringement, prompting Maglula to file suit against the Jeff Bezos-founded company.

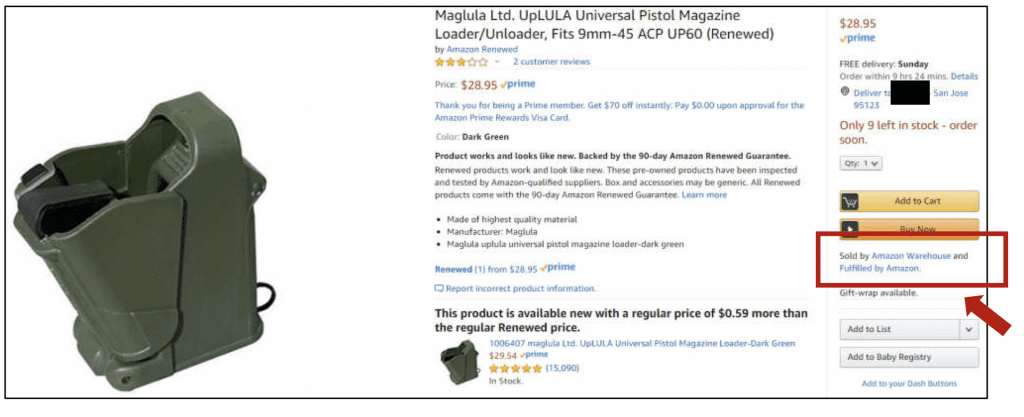

Aside from struggling to get Amazon to remove the allegedly infringing products (some of which listed “Amazon Warehouse” as the seller and all of which “Fulfilled by Amazon”), Maglula alleged that the contact information that Amazon provided for the third-party sellers at issue was largely “nonfunctional,” with at least some of the information being erroneously linked to individuals who “were victims of documented identity theft.” Ultimately, Maglula argued that Amazon made it “impossible” to bring the third-party sellers “to court and investigate sources of the knock-offs.”

And in a bid to preemptively chip away at Amazon’s longstanding (and largely successful) argument that it is not the “seller” of the products that appear on its marketplace and thus, is shielded from liability, Maglula claimed that Amazon is more than a mere middleman, as it “controls all aspects of the sales process with its partners,” and enjoys the exclusive right to “suspend, prohibit or remove product listings” and to “receive all proceeds from all of [the] sales on behalf of its partners” on the marketplace site.

Following failed attempts by Amazon to compel arbitration and then to have the case transferred to a federal court in its native Seattle, Judge Liam O’Grady of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia handed Amazon another loss in May 2021. In a three-page order on Amazon’s motion for summary judgment, Judge O’Grady held while Amazon “identified apparent weaknesses in some of Maglula’s supporting evidence,” even those weaknesses were unlikely to make “one iota of difference to a jury” in light of the “overwhelming” evidence of “unlawful counterfeiting” at play.

Among other things, the court shot down Amazon’s argument that Maglula should not be permitted to make sweeping claims of infringement about “thousands of disparate products from various third-party vendors and manufacturers” without showing on a “product-by-product basis what marks are at issue or how the alleged infringement occurred.” In his order, Judge O’Grady held that Maglula bears no such burden, and instead, is only required to show that a “representative sample has been infringed” in order to survive a motion for summary judgment.

Characterizing the matter as a “straightforward counterfeit case,” Judge O’Grady stated that “this is simply not a case where Amazon can avoid liability” (at least not in the summary judgment phase), noting that the retailer “proceeded to sell [the infringing Maglula goods] online as genuine products,” despite being notified “on multiple occasions, to no avail, that it was selling counterfeit goods of inferior quality and ruining Maglula’s business.”

A “Straightforward” Case of Counterfeits

On the heels of the court finding that genuine issues of material fact existed in connection with each of the causes of action (including whether Amazon and its third-party sellers have a relationship that allows for Amazon to be vicariously liability for the alleged counterfeits and infringement), thereby, making summary judgment inappropriate, and in the wake of court-ordered mediation, the parties settled the matter in its entirety in December.

Finnegan’s Jeffrey Berkowitz and David Mroz, who acted as counsel for Maglula, have since hailed the court’s summary judgment decision as unprecedented, stating that the finding that Maglula’s case against Amazon was a “straightforward counterfeit case” is something that no other court has held when it comes to Amazon and its third-party platform. That determination could prove to be significant in light of the fact that over 50 percent of Amazon’s sales are generated by third-party sellers on its marketplace, and given enduring arguments that “Amazon does a lot more to broker the arrangements between buyers and sellers” than marketplaces like eBay, which avoided direct and contributory liability in a trademark case waged against it by Tiffany & Co. over a decade ago.

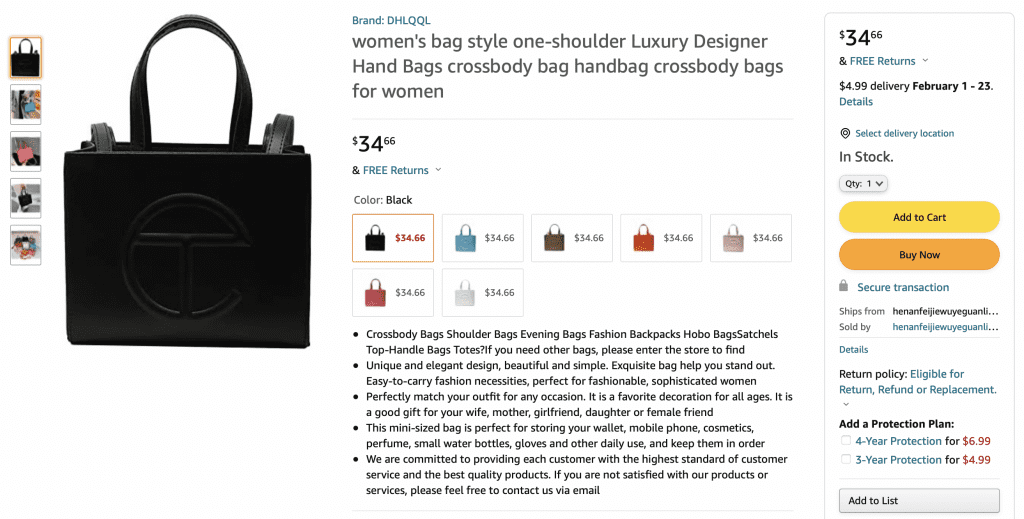

For a point of reference, some of the questionable third-party listings on Amazon currently include trademark infringing Gucci Dionysus bags, counterfeit Jacquemus offerings, infringing Telfar shopping bags and droves of copycat Bottega Veneta wares.

Maglulga – which asserted in its complaint that Amazon has become “so overrun with counterfeit products, and its meager efforts to address this problem have been so ineffective, that counterfeit products are now leaving Amazon warehouses all over the United States at an alarming rate” – is not the only plaintiff to have pursued Amazon for infringement in the not-too-distant past.

The Cashmere and Camel Hair Manufacturers Institute sued Amazon and third-party seller CS Accessories in November 2021 on trademark grounds, accusing the defendants of offering up counterfeits and deceiving consumers by offering up products that it falsely marketed as “100% Cashmere,” and claiming that even after alerting Amazon of the issue, the retailer failed to promptly or “effective” action to remove the fake cashmere products. The case settled last month but not before a federal district court judge in Boston permanently barred CS Accessories from advertising or selling products falsely labeled as cashmere.

The case is Maglula, Ltd. v. Amazon.com, Inc., 1:19-cv-01570 (E.D.Va.)