A potentially high-stakes clash has broken out between WHOOP and a Chinese manufacturer of wearable devices. In a newly-filed lawsuit, Boston-based WHOOP accuses Shenzhen Lexqi Electronic Technology of making and selling knockoffs of its screenless fitness tracker. At the core of the trade dress and unfair competition case – the latest to pit a U.S. tech entity against a Chinese rival – is the question of whether WHOOP’s minimalist design has become distinctive enough to warrant legal protection as an indicator of source.

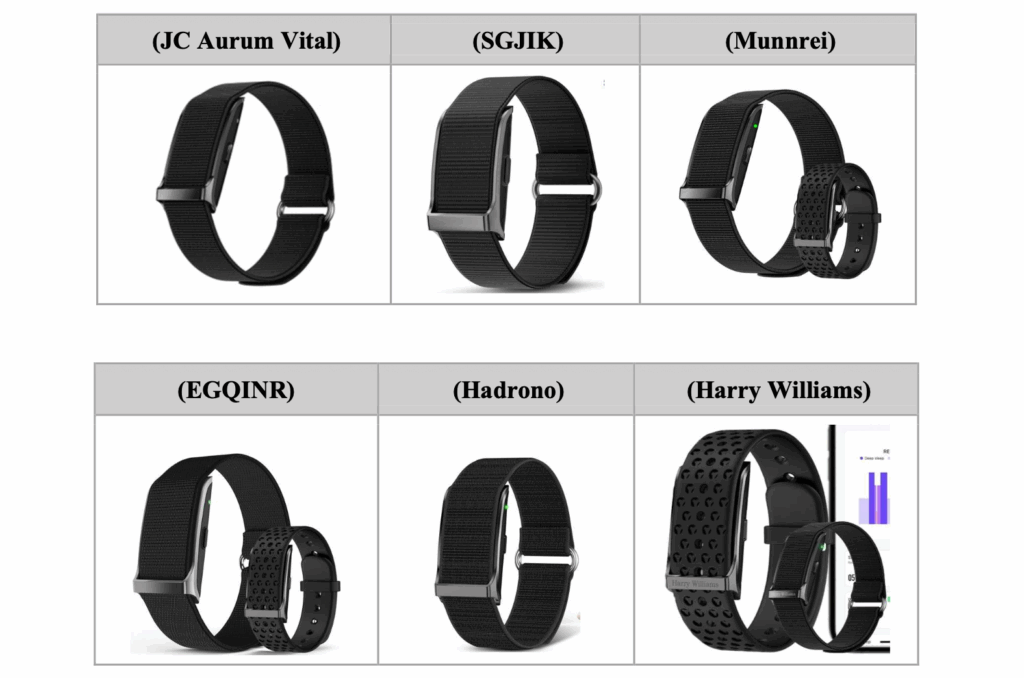

According to the September 22 complaint that it filed in federal court in Massachusetts, Shenzhen Lexqi (“Lexqi”) has deliberately copied WHOOP’s design and is pushing the lookalike device into the U.S. market via Amazon storefronts with names like “SGJIK” and “EGQINR.” WHOOP alleges that Lexqi’s wearable product is “a wholesale copy” of its faceless band, which has come to serve as the brand’s signature design and a key differentiator in the crowded wearable tech market.

Despite sending cease-and-desist letters in July, WHOOP says Lexqi has doubled down on its alleged infringement. Several storefronts confirmed that Lexqi as the manufacturer of their offerings and produced “authorization letters” allegedly signed by the company, granting global rights to sell the infringing devices. WHOOP also highlights that Lexqi filed a U.S. design patent application in 2024 for a lookalike device – years after WHOOP first introduced its trade dress – and obtained FCC equipment authorizations for the bands, signaling intent to distribute in the U.S.

With the foregoing in mind, WHOOP sets out claims of trade dress infringement, false designation of origin, and unfair competition, and is seeking damages, disgorgement of profits, and broad injunctive relief to bar Lexqi from further infringement.

An Indicator of Source?

At the heart of WHOOP’s case is its claim that its design is more than just aesthetic. It acts as an indicator of the WHOOP brand. Portraying the device’s look as non-functional and as having acquired distinctiveness through extensive promotion and consumer recognition, WHOOP is laying the groundwork for its argument that consumers associate the screen-less band with a single source.

>> The trade dress in a nutshell: WHOOP describes its wearable device trade dress as consisting of a three-dimensional configuration featuring a U-shaped clasp with the word WHOOP on the crossbar, hinged sides that close over a rectangular sensor, and a strap that connects to the clasp and wraps fully around the device to lay flat against the sensor and snug on the wearer’s wrist. The word WHOOP – which appears in the device, itself – is not part of the claimed trade dress.

WHOOP points to a decade of investment in its best-selling product as the foundation of its trade dress claim. The company says it has devoted “substantial time, money, and effort” to advertising its device across print, television, digital platforms, and social media, running campaigns aimed at making the strap recognizable by its design alone. Those efforts have been bolstered by endorsements from famed athletes and amplified by widespread media coverage. WHOOP argues that consumers can identify its devices by appearance alone – citing People and other outlets recognizing Prince William’s strap during the 2024 UEFA EUROs as WHOOP product even without a visible logo. Social media accounts like “Whoop in the Wild” and Reddit “WHOOP sightings” threads, it adds, further demonstrate that consumers view the design, itself, as a source identifier.

It is worth noting that WHOOP broadly refers to the commercial success – and widespread marketing – of its product. However, the company does not put forth quantitative information, such as sales data, advertising expenditures, or consumer survey evidence, which courts often treat as central to the secondary meaning inquiry, which could leave its claim more susceptible to challenge.

It does cite evidence of actual consumer confusion, including Amazon reviews referring to Lexqi’s knockoff as a “WHOOP band,” and one storefront admitting it mistakenly listed the infringing product as authentic WHOOP merchandise.

The Bigger Picture

With WHOOP positioning its wristband as more than a fitness tracker – but a cultural marker and wellness status symbol – the company is testing how far trade dress can stretch to shield product design. Trade dress remains an important, if carefully scrutinized, tool for protecting brand identity, but it poses particular challenges in the wearable tech realm, where design elements often overlap with functional ones. WHOOP’s case sits squarely in this tension: it must prove that its minimalist clasp-and-strap configuration is non-functional and that years of promotion and recognition have imbued it with distinctiveness.

At the same time, with Lexqi holding a pending U.S. design patent and insisting on its right to sell, the dispute also illustrates how global manufacturers leverage IP filings to shield themselves – and how U.S. brands are increasingly forced to litigate across both commerce and culture. Lexqi’s actions show how manufacturers can use U.S. intellectual property and regulatory filings as both a shield and a sword. By seeking design patent protection and obtaining FCC equipment authorizations, the Shenzhen-based company is doing more than just selling a lookalike device; it is angling to cloak that product in the legitimacy of American IP and regulatory systems.

This strategy reflects a broader pattern of Chinese manufacturers entering the U.S. market through online storefronts and third-party sellers, while simultaneously seeking U.S. patents, trademarks, and regulatory approvals, a combination that can complicate enforcement for domestic brands.

For WHOOP, this means the burden is twofold. The company must not only stop what it views as a wholesale copy of its product but also dismantle the legitimacy Lexqi is trying to build through those filings.

The case is WHOOP, Inc. v. Shenzhen Lexqi Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., 1:25-cv-12690 (D. Mass.).