Sotheby became one of the latest establishment names in art to dive into non-fungible tokens – “NFTs” – by way of its collaboration with anonymous digital artist Pak and NFT marketplace Nifty Gateway. The auction house sold The Fungible Collection, a “novel collection of digital art redefining our understanding of value,” for more than $17 million, with some pieces, such as “The Switch,” a monochrome 3D construction that is going to be changed by the artist at some unspecified moment in the future, receiving bids well in excess of $1 million.

For the uninitiated, NFTs are tokenized versions of assets that can be traded on a blockchain, the digital ledger technology behind cryptocurrencies like bitcoin and Ethereum. While one bitcoin is directly interchangeable with another, meaning that the currency is fungible, NFTs are the opposite, which means that the underlying assets are unique in some way and thus, cannot be exchanged in a like-for-like capacity. This uniqueness – and enduring market hype – is what enabled Christie’s to sell digital artist Beeple’s “Everydays” NFT in March for an eye-watering $68 million. For those that do not have that sort of money, NFTs are also being used for trading collectables like baseball cards, computer gaming items, and fashion goods.

Bubble trouble?

The excitement around NFTs feeds a similar narrative to other recent price surges, such as GameStop and dogecoin, in that these are speculative bubbles. Look no further than celebrities like musician Grimes and YouTube star Logan Paul, who have released their own flagship NFTs to ride the wave. But speculation may be the name of the game, as even Vignesh Sundaresan, the entrepreneur who bought Beeple’s record-breaking artwork, says that he sees investing in NFTs as a “huge risk” and “even crazier than investing in crypto.”

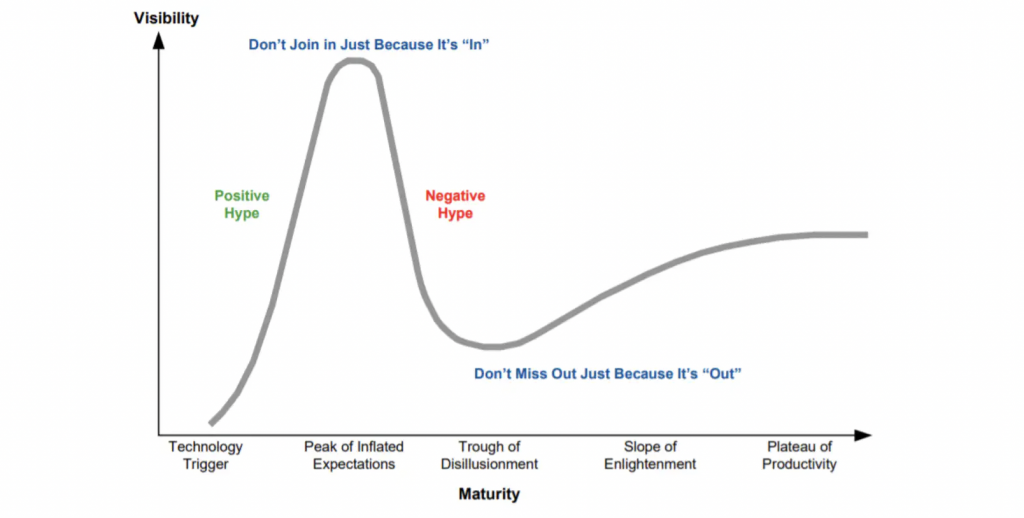

However, history tells us to be careful about dismissing NFTs as a passing fad, since the importance of technological innovations often becomes clearer once the hype dies down. Many commentators dismissed the influx of tech companies around the dotcom bubble of the late 1990s, and the first wave of mass cryptocurrency enthusiasm in 2017, only to be proven hopelessly wrong when Amazon and bitcoin re-emerged. NFTs, themselves, are actually well down from their highs, with a 70 percent drop in average price since February. Perhaps this is less the bursting of a bubble than a “weeding out” of gimmicky tokens now that the initial hype has begun to die down.

This phenomenon is captured well in U.S. consultancy Gartner’s hype cycle, which illustrates the typical progression of a new technology. With NFTs, we are probably emerging from the “peak of inflated expectations” on a journey towards the same “plateau of productivity” that Amazon reached a long time ago. This ties in with what Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter said about why capitalism works. Schumpeter viewed capitalism as a relentless churn of old into new, as the latest and most innovative enterprises replace those that came before – he called this “creative destruction.” In this light, NFTs are the newcomers challenging how we perceive and register ownership of assets. And the tension between innovation and incumbency also contributes to the skepticism that always surrounds such new technologies.

What happens next

NFTs create opportunities for new business models that did not exist before. Artists can attach stipulations to an NFT – by way of a smart contract – that ensures they get some of the proceeds every time it gets resold, meaning they benefit if their work increases in value. Admittedly football teams have been using similar contractual clauses when selling on players for a while, but NFTs remove the need to track an asset’s progress and enforce such entitlements on each sale.

New art platforms, such as Niio Art, are able to demonstrate in a really simple way that they own digital works. When customers borrow or buy art from the platform, they can display it on a screen in the knowledge that there is no issue with copyright or originality because the NFT and blockchain ensures that ownership is authentic. Still yet, NFTs give musicians the potential to provide enhanced media and special perks to their fans. And with sports memorabilia, between 50 percent and 80 percent of items are thought to be fake. Linking these items to NFTs with a clear transaction history back to the creator could help to overcome this counterfeiting problem.

Beyond these fields, the potential of NFTs goes even further because they change the rules of ownership to some extent. Transactions in which ownership of something changes hands have usually depended on layers of middlemen to establish trust in the transaction, exchange contracts and ensure that money changes hands. None of this will be necessary in future. Transactions recorded on blockchains are reliable because the information cannot be changed. Smart contracts can be used in place of lawyers and escrow accounts to automatically ensure that money and assets change hands and both parties honor their agreements. NFTs convert assets into tokens so that they can move around within this system. This has the potential to completely transform markets like property and vehicles, for instance.

NFTs could also be part of the solution in resolving issues with things like land ownership. Only 30 percent of the global population has legally registered rights to their land and property. Those without clearly defined rights find it much harder to access finance and credit. Also, if more of our lives are spent in virtual worlds in future, the things that we buy there will probably be bought and sold as NFTs, too, which could prove a boon for luxury goods companies.

There will be many other developments in this decentralized economy that have yet to be imagined. What we can say is that it will be a much more transparent and direct type of market than what we are used to. Those who think they are seeing a flash in the pan are unlikely to be prepared when it arrives.

James Bowden is a Lecturer in Financial Technology at the University of Strathclyde. Edward Thomas is a Jones Lecturer in Economics at Bangor University. (This article was initially published by The Conversation)