The widespread counterfeiting activities that well-known trademark holders are forced to face off against online is making it more difficult – and expensive – for bona fide brands to fairly compete, Chanel asserts in a new trademark infringement and counterfeiting lawsuit. According to the complaint that it filed in a Florida federal court in July, Chanel alleges that a group of defendants – which are identified exclusively by 25 different Wish.com Merchant ID numbers, such as 607E22E7DE02EC0FA2663E4E – are “using identical copies” of one or more of its trademarks for subpar quality goods in order to “dupe and confuse the consuming public,” while also earning “substantial” profits at its expense.

Setting the stage in its complaint, Chanel asserts that “like many other famous trademark owners, [it] suffers ongoing daily and sustained violations of its trademark rights at the hands of counterfeiters and infringers,” such as the defendants, who are “directly and unfairly competing with [its] economic interests” and causing it “irreparable harm and damage” by way of their sale of counterfeit and infringing Chanel-branded products – from handbags and wallets to belts and other accessories.

Chanel alleges that the defendants are using its “famous name and trademarks to drive consumer traffic to their e-commerce stores operating under the Merchant IDs, thereby increasing the value of those Merchant IDs and decreasing the size and value of Chanel’s legitimate marketplace and intellectual property rights at Chanel’s expense.” At the same time, the defendants are operating behind the “false and/or misleading [identifying] information” that they provided to the relevant e-commerce platforms, namely, Wish.com, in order to obscure their real identities and avoid liability for their “wrongful conduct.”

In addition to potentially confusing consumers as to the source or nature of the counterfeit products, Chanel claims that damage caused by the defendants runs deeper, and that they are harming it and the consuming public by “depriving [it] and other third parties of their right to fairly compete for space within search engine results and reducing the visibility of Chanel’s genuine goods on the web.” According to Chanel, in furtherance of their offering up for sale and actual sale of the allegedly infringing goods, defendants’ “individual seller stores are indexed on search engines and compete directly with Chanel for space and consumer attention in the search results,” which is problematic, as “visibility on the Internet, particularly via search engines such as Google, Yahoo!, and Bing is important to Chanel’s overall marketing and consumer education efforts.”

Beyond that, Chanel argues that the defendants are “causing an overall degradation of the value of the goodwill associated with the Chanel trademarks, and increasing Chanel’s overall cost to market its goods and educate consumers about its brand via the Internet.” In order to maintain the valuable goodwill that its trademarks enjoy among consumers, and to combat “the indivisible harm caused” by parties like the defendants, Chanel claims that it spends “significant monetary resources in connection with trademark enforcement efforts, including legal fees, investigative fees, and support mechanisms for law enforcement, such as field training guides and seminars.”

All the while, Chanel states that it had built and maintains its reputation as a purveyors of “high-quality goods,” thanks to its consistent use of the marks, its “carefully monitor[ing] and polic[ing] of the use of [its] marks, and its pattern of “expend[ing] substantial resources developing, advertising, and otherwise promoting [its] marks.” All the while, Chanel asserts that annual sales of products bearing its famous trademarks “have totaled in the hundreds of millions of dollars within the United States, alone” in recent years, which is a testament to the fact that “members of the consuming public readily identify merchandise bearing or sold using the Chanel marks, as being high quality goods sponsored and approved by Chanel.”

Chanel says that its efforts to maintain its valuable trademarks come amid the “exponential growth of counterfeiting over the Internet, including through online marketplace platforms and social media websites,” which coexists with the market for genuine Chanel products and its advertising of those goods.

Setting out claims of trademark counterfeiting and infringement, unfair competition, and false designation of origin, Chanel argues that the defendants “are engaging in the above-described illegal counterfeiting and infringing activities knowingly and intentionally or with reckless disregard or willful blindness to Chanel’s rights for the purpose of trading on Chanel’s goodwill and reputation,” and that the “natural and intended byproduct” of the defendants’ combined actions is “the erosion and destruction of the goodwill associated with the Chanel name and associated trademarks,” the brand argues. And still yet, Chanel asserts that the defendants are also contributing to “the destruction of the legitimate market sector in which [it] operates.”

With the foregoing in mind, Chanel is seeking monetary damages to be determined at trial and permanent injunctive relief to bar the defendants from “manufactur[ing], importing, advertising or promoting, distributing, selling or offering to sell their counterfeit goods,” among other things.

The Secondary Market

An otherwise relatively routine anti-counterfeiting complaint, Chanel’s suit is striking, nonetheless, if we consider the claims of consumer confusion. Chanel asserts (as most plaintiffs do in similar infringement/counterfeiting complaints) that the defendants’ “infringing activities are likely to cause confusion, deception, and mistake in the minds of consumers before, during, and after the time of purchase.” While there may be arguments to be made about point-of-sale confusion, the notion of confusion after the fact is the most interesting here, as it seems unlikely (at least to me) that even unsophisticated consumers would confuse the nature of authentic Chanel bags, for instance – which routinely retail for far upwards of $1,000 – with the very cheaply-priced ones being offered up by the defendants.

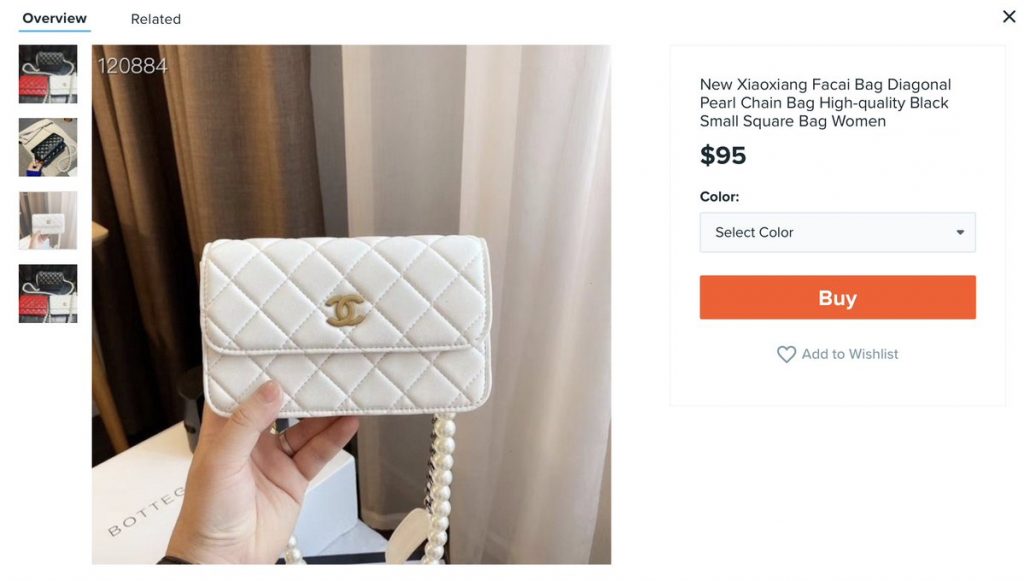

The defendants’ whose Wish.com listings were still accessible following the filing of Chanel’s complaint consist of logo-bearing handbags for $95, for instance, and belts for $28 (i.e., hundreds, if not thousands of dollars less than Chanel price points).

While confusion at the point of initial sale is hard to imagine due to the differing price points at play, among other things, it is notdifficult to imagine confusion in a post-sale capacity. Moreover – and this is the most compelling point – assuming that the quality of the goods at issue is high enough to pass muster (and there is no saying that they are in the case at hand), it is not impossible to picture them being mixed into the market of authentic goods, including those being offered up and sold by way of the secondary market, where authentication effects can be subpar, as Chanel argues in other, unrelated lawsuits.

It is on this ground – paired with enduring intelligence that many counterfeit operations are making strides in terms of their sophistication and thus, that the counterfeit goods are readily increasing in quality – that Chanel’s argument appears to be the most persuasive.

The role that the burgeoning multi-billion-dollar secondary market stands to play when it comes to outright – but high quality – counterfeit goods, as well as authentic goods that are modified to the point of alleged infringement, is increasingly being taken into account in the complaints being filed by brands. While Chanel does not explicitly make this point, Nike has been in recent suit, including the one that it filed in March against MSCHF, asserting that the company’s Satan sneakers “will continue to cause confusion in the marketplace, including but not limited to initial interest confusion, post-sale confusion, [and] confusion in the secondary sneakers markets.” Nike has since doubled-down on the point in another customization-centric lawsuit.

Given Chanel’s enduring fight against the marketing and sale of its products by resellers (and their ability to properly authenticate its products), it would not be surprising if the brand is considering the potential for confusion after the fact – i.e., in the secondary market – and if it specifically points to such risks in the future.

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. 607E22E7DE02EC0FA2663E4E, et. al., 0:21-cv-61265 (S.D.Fla).