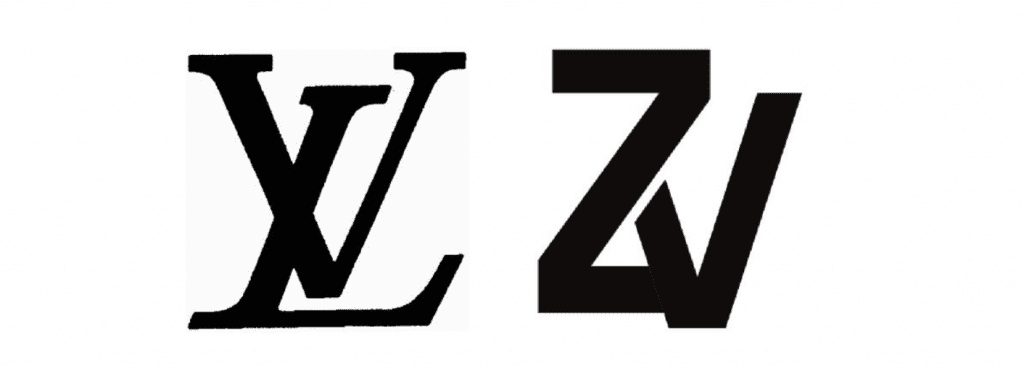

Louis Vuitton has been handed a loss in a two-year-long legal battle against Zadig & Voltaire, in which it (unsuccessfully) argued that the fashion brand is piggybacking on the reputation of the Louis Vuitton brand and confusing consumers by way of its adoption and widespread use of a “lookalike” ZV logo on handbags. Siding with Zadig & Voltaire in February, the Paris Judicial Court determined that despite Louis Vuitton’s claims to the contrary, the “very low similarity” between the French fashion brands’ interlocking letters trademarks, including the “different construction and arrangement,” means that consumers are unlikely to associate – or confuse – the respective companies’ marks.

Some Background: In the complaint that it filed in January 2021, Louis Vuitton argued that Zadig & Voltaire is likely to confuse consumers and to “unduly take advantage of the reputation of [the Louis Vuitton] brand” by using a logo that features the letters ZV presented in “an intertwined [manner] with a downward shift of the V,” and that is distinct from previous versions of the logo used by the company. When Zadig & Voltaire refused to halt its use of the logo after receiving a cease-and-desist letter from Louis Vuitton in August 2020 (and instead, argued that its logo is different from Louis Vuitton’s), the luxury goods titan filed suit. (For another LV logo clash in the European Union, you can find that here.)

In furtherance of its infringement and parasitism claims, Louis Vuitton asserted that its traditional LV logo – which it has used since the 1800s, “enjoys exceptional worldwide fame, [something] has already been recognized in court,” and its newer LV “Twist” logo is also “renowned among the ‘public targeted by this mark.’” Louis Vuitton alleged that fame for the LV “Twist” logo stems from “the success of the Twist bag on which the mark appears” and the extent of its advertising campaigns that feature the mark and third-party media attention to bags that include the mark.

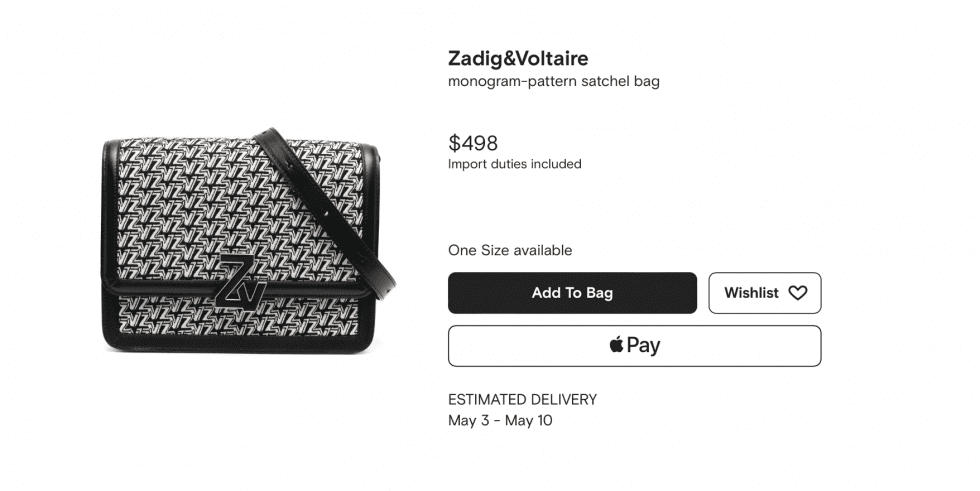

Setting out an infringement claim, Louis Vuitton argued that Zadig & Voltaire’s logo is visually, phonetically, and conceptually similar to its own, as they “both consist of two letters, written in capital letters and one of which is the same, which have almost the same character size, and which overlap with a slight height shift,” among other things. Louis Vuitton further claimed that Zadig & Voltaire’s “massive use” of the lookalike logo “qualifies as parasitism when taken in context” – namely, its use as a centrally-positioned clasp on handbags – and when “associated with the use of the term ‘monogram.’” (Louis Vuitton noted that Zadig refers to products bearing a repeating pattern of the logo as “Monogram,” which is problematic, as “the Louis Vuitton canvas created in 1896 is, itself, known as ‘Monogram Canvas.’”)

Zadig & Voltaire pushed back against Louis Vuitton’s claims on multiple fronts, arguing primarily that it has been using its initials in a commercial capacity since 1997 and has been using them “as a brand and logo” since 2005 in furtherance of an effort to “assert its identity and develop its range [of branding], and not to take advantage of the reputation of Louis Vuitton.” At the same time, the company attempted to chip away at Louis Vuitton’s claims by arguing that it has not used the ZV logo more prominently than its other branding and that its brand name is “always identifiable in communications involving the disputed logo.”

In terms of the alleged similarity of the marks, Zadig maintained that the marks “are composed of different letters,” which are not the same size; are “stylized and presented differently, pronounced differently, and refer, conceptually, respectively to Louis Vuitton and Zadig & Voltaire,” which occupy different spaces in the market. Additionally, counsel for Zadig argued that affixing a logo consisting of a brand’s initials to the exterior of a handbag is “frequent,” which prompts the consuming public to “be attentive to differences” between brands’ offerings.

Still yet, Zadig & Voltaire “expressly dispute[d]” the alleged fame of Louis Vuitton’s new “Twist” LV logo, stating that fame/reputation is assessed for each mark individually, and that Louis Vuitton “only invokes elements relating to the reputation of the old logo.”

Reputation – First reflecting on Louis Vuitton’s allegations about the reputation of its LV logo, the court said that there is no dispute over the fame/reputation of the traditional LV logo in light of “the extreme intensity of use on very variable media, in particular through notoriously very extensive advertising, and the commercial success of the uses [of the mark].” While Louis Vuitton’s consumers consist of a relatively “small group of customers (the wealthiest) among the general public,” the court stated that “the extent of the communication and the resonance [of the LV logo] goes far beyond this single group” to the general public, and thus, the mark has “a strong reputation.”

On the other hand, the newer LV logo has only been used for 8 years on “a relatively limited number of models of handbags (which Louis Vuitton groups under the name Twist).” The fact that Louis Vuitton claimed that these handbags were “the subject of an intense advertising campaign” is not sufficient, in itself, to demonstrate that the mark is known to a significant part of the public concerned, the court held. Louis Vuitton did not demonstrate how this mark “would have become, in such a short time, known to a significant part of the general public,” the court stated, and instead, provided little evidence “beyond a number of advertising photographs showing a model carrying a bag bearing the mark.”

Moreover, the court took issue with the fact that Louis Vuitton attempted to claim commercial success of the Twist collection in purely “vague” terms, referring to the “dazzling success” of the Twist collection, for example, and providing examples of “favorable media coverage, without the articles invoked making it possible to demonstrate that a significant part of the general public is familiar with the bags.” These elements “are, indeed, all the less likely to prove the reputation of the mark, itself, since, while it is very stylized, the only use that is alleged is that of decorative clasp (admittedly very visible) on the bags,” the court asserted, noting that “the chances of the public seeing and retaining this sign as a mark are low.”

The reputation of Louis Vuitton’s newer LV logo “has, therefore, not been demonstrated,” the court found.

Infringement – The court similarly sided with Zadig & Voltaire in finding that there is no infringement at play. For there to be infringement, the court held that there must be “a certain degree of similarity between the marks” that enabled the public to “make a connection between them.” No such “link” exists here, as while the goods are similar, consumers are not likely to associate the marks, themselves, in part because the key similarity between them is the use of two capital letters of similar size, and this is common since it is “the very principle of a monogram.”

Against this background, the court declared that “it would be necessary, in order for the public to associate the marks in question despite their very low similarity and their different construction and layout, for the mark LV to be so famous that the public associates with it any other two-letter monogram containing a V.” The issue here is that such an association “is not demonstrated, nor even alleged, [by] Louis Vuitton.” It follows then, according to the court, that “even for identical goods, the marks at issue are too dissimilar for the relevant public, namely the general public, to establish a link between them,” the court holds. “This excludes any possibility of damage to reputation, and justifies the rejection of infringement claims.”

Parasitism – Finally, the court found that Louis Vuitton “does not explain how the use of initials as a bag clasp … would be the fruit of particular investments that confer on it individualized economic value.” Beyond that, the court noted that Louis Vuitton also fails to demonstrate or even alleges that it is the “only one – or was the first” to make use of its initial in this way or “how this single idea would belong to it.” As for the use of the term “monogram” (by a French company in English), the court stated that “it is certainly unusual, but cannot be appropriated by Louis Vuitton, even when associated with the actual use of a monogram for leather goods.”

As such, the court held that “the disputed facts, both individually and taken as a whole, do not characterize the appropriation of an investment identified by [Louis Vuitton], and accordingly, the claims based on parasitism are also dismissed.”

In light of its loss, the court ordered Louis Vuitton to compensate Zadig & Voltaire for its costs, which the court estimated to be 30,000 euros. Likely not the end of this battle, Jérôme Tassi, a partner at Paris-based firm AGIL’IT, says that the court’s decision “seems very strict on the assessment of the infringement of the reputation mark,” and thus, there will “probably be an appeal of the judgment” by the luxury goods giant.

The case is Louis Vuitton Malletier v. ZV France, 2023, 21/02820.