Late last week, as Off-White was landing on the receiving end of one trademark infringement lawsuit, which streetwear brand Walker Wear filed against it and retailers Saks and Farfetch, it was settling another. According to the docket in the trademark case that Off-White filed against ice cream chain Afters Ice Cream later last year, accusing the defendant of offering up merch and using “retail fixtures, signage, [and] interior décor” that is meant to “confuse consumers into believing that [its] products are Off-White products and/or that [it or its] business is affiliated with Off-White,” the parties have managed to settle their differences out of court, prompting counsel for Virgil Abloh’s brand to alert the court on August 20 that the matter has been settled.

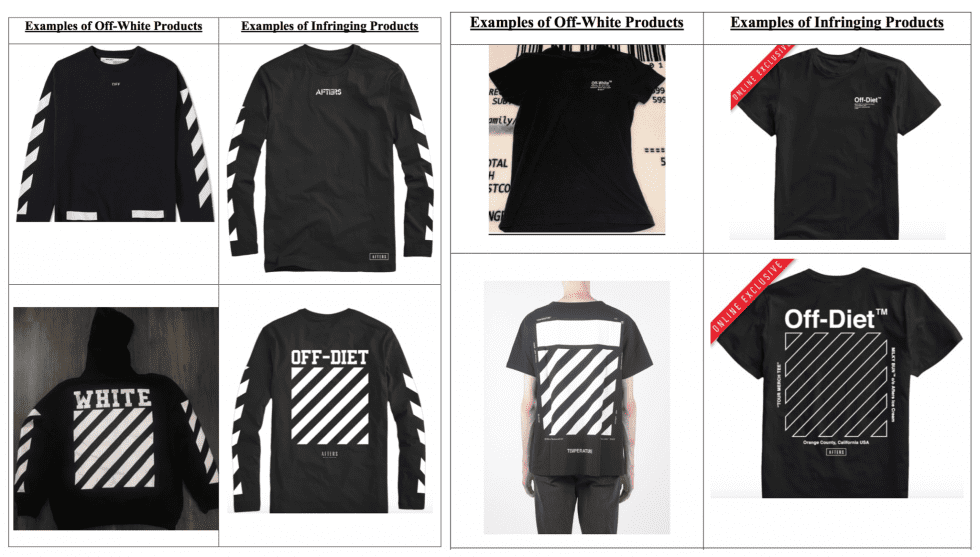

In the complaint that it filed in a California federal court in November 2020, Off-White argued that Afters – a premium handcrafted ice cream chain founded by Scott Nghiem and Andy Nguyen, both of whom have “a background in clothing and/or streetwear” – was running afoul of trademark law by “manufacturing, advertising, marketing, promoting, distributing, displaying, offering for sale, and/or selling products” that make use of “one or more of Off-White marks,” and affixing “confusingly similar [or] identical” signage and interior decoration to its stores and pop-up outposts.” According to Off-White, such unauthorized uses of Off-White’s marks came in furtherance of the California-based chain’s attempt to confuse consumers into believing that it is connected in some way to Off-White when no such ties between the two companies.

Off-White pointed to “significant common law trademark” rights for its name and various logo marks, and five federal trademark registrations for its “15 alternating parallel diagonal lines of varying sizes” marks – which are mostly registered for use on garments and accessories, but one of the registrations includes use in connection with “retail store services featuring apparel, footwear, fashion and clothing accessories,” among other things – as the basis for its claims.

Afters swiftly shot back with some claims of its own, and among the laundry list of affirmative defenses that Afters cited in its January 2021 answer? Parody. As we previously noted, parody appears as though it could be a relevant argument since Afters did not merely copy-and-paste the Off-White name and striped branding for its t-shirts and sweatshirts on its own; it has included some additional elements. For instance, instead of using the full Off-White name on one of its t-shirt styles along with the diagonal stripe square, the Afters garments read, Off-Diet, a seeming play on the calorie count of ice cream. It has taken similar light-hearted jabs at other buzzy brands – from Anti Social Social Club (its version is “Anti Diet Diet Club”) to Kanye West’s Sunday Service, complete with “Ice Cream is King” and “Sundae Service” taglines. Since the case got its start, Afters released additional merch that plays on Off-White’s use of quotation marks.

The case has ultimately come to a close before any substantive findings with regards to either Off-White’s infringement claims or any of Afters’ defense. It would have been interesting to see Afters make the case that it should be shielded from trademark infringement liability due to the parodic nature of its offerings.

Other Parody Cases

The Off-White case – and Afters’ preliminary lodging of a parody defense – follows from a number of headline-making parody cases, which have, as King & Spalding partner Katie McCarthy put it, “illustrated the difficulties brands face when pursuing claims against trademark parodies in the U.S.”

One of the most recent of these cases came out of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, which saw Jack Daniel’s wage trademark infringement and dilution claims against dog toy-maker VIP Products LLC for allegedly hijacking its trade dress and bottle design for a chew toy bearing the name “Bad Spaniels.” On the heels of the district court finding for Jack Daniel’s on all claims and entering a permanent injunction in its favor, the Ninth Circuit concluded in March 2020 that while VIP Products used Jack Daniel’s trademarks to sell its dog toys, the “humorous message” conveyed by the toy makes the use “expressive” and protected under a heightened First Amendment standard as a result.

In response Jack Daniel’s sought Supreme Court intervention, pointing to mixed treatment by lower courts of trademark infringement claims involving the use of famous marks on commercial products in a “humorous” capacity. In a September 2020 certiorari petition, which was ultimately tuned down by SCOTUS, Jack Daniel’s asked the nation’s highest court to determine “whether a commercial product using humor is subject to the same likelihood-of-confusion analysis applicable to other products under the Lanham Act, or [whether it] must receive heightened First Amendment protection from trademark-infringement claims, where the brand owner must prove that the defendant’s use of the mark either is ‘not artistically relevant’ or ‘explicitly misleads consumers.’”

The Supreme Court’s refusal to grant certiorari in January 2021 left the lower court’s decision – which shielded the toy from trademark liability in accordance with the First Amendment – firmly intact.

That development came almost 15 years after the Fourth Circuit sided with unaffiliated dog toy maker Haute Diggity Dog in the trademark suit waged against it by Louis Vuitton, which centered on a number of Haute Diggity Dog toys that resembled Louis Vuitton products, called “Chewy Vuitton.” The court found in favor of Haute Diggity Dog on the basis that the dog toys were obvious parodies – which the court defined as “a simple form of entertainment conveyed by juxtaposing the irreverent representation of the trademark with the idealized image created by the mark’s owner,” which conveys “two simultaneous and contradictory messages: that it is the original, but also that it is not the original and is instead a parody” – and not likely to confuse customers.

And more recently, in a separate Louis Vuitton-initiated parody fight, the luxury goods brand sued My Other Bag, Inc. in a New York federal court in 2014 over a line of canvas tote bags that replicated a number of Louis Vuitton’s iconic designer handbags. The Second Circuit sided with My Other Bag, issuing a summary order in December 2016, in which it affirmed the district court’s decision – and its finding that the My Other Bag tote bags were shielded from Louis Vuitton’s trademark dilution claim by the parody defense, as well as from its trademark infringement claim due to a low likelihood of consumer confusion – in favor of My Other Bag.

Speaking specifically to parody, the Second Circuit determined that the cotton tote bags co-opted Louis Vuitton’s handbag designs and the trademark patterns that come with them (the Toile Monogram and Damier print, for instance), and did so in a way that was recognizable. At the same time, the defendant’s bags still presented a “conscious departure” from Louis Vuitton’s offerings so consumers would know the bags were not, in fact, Louis Vuitton bags, thereby, giving rise to a successful claim for parody.

The court noted the significance of the fact that My Other Bag was not using Louis Vuitton’s trademarks in order to indicate the source of its own bags, and instead, its own brand was the “undisputed designation of source” of the tote bags, as demonstrated by the large “My Other Bag . . .” writing on one side of the totes.

In seeking Supreme Court intervention, which never came, counsel for Louis Vuitton argued, among other things, that “permitting an entire business model premised on the exploitation of famous marks to sell knock-off products is flatly at odds with Congress’s intent to protect famous marks from dilution.”

“Sold Out”

Back in the Off-White v. Afters case, the terms of the parties’ settlement agreement are confidential, with the settlement notice filed by Off-White merely stating that “the parties have reached a settlement and have executed a settlement agreement, [and] pending the occurrence of certain conditions precedent, the parties expect to file a stipulation of dismissal no later than September 10, 2021.”

As for one potential condition that Afters might have to make good on? Stopping its sale of the allegedly infringing wares. It is worth noting that as of the time of publication, Afters still displays photos of its merch lookbook on its site, which include the allegedly infringing wares, but the “swag” section of its site lists all of the products as sold out.

The case is Off-White LLC v. Afters Ice Cream, Inc., 8:20-cv-02121 (C.D.Cal.).