Chanel and What Goes Around Comes Around (“WGACA”) are currently embroiled in a federal jury trial in a case that centers on the luxury brand’s claims that the resale company has tried to “deceive consumers into falsely believing [that it] has some kind of affiliation with Chanel or that Chanel has authenticated [the pre-owned] goods [it is offering up] in order to trade off of Chanel’s brand and goodwill.” At the same time, Chanel claims that the New York-headquartered reseller has offered up infringing Chanel-branded products – from coveted handbags to hundreds of display items, the latter of which were never meant for sale.

A couple of the most critical issues at play come in the form of defenses waged by WGACA, which center on the basic premise that anyone can offer up authentic trademark-bearing products for sale – and use the original manufacturer’s name, logo, etc. in connection with those subsequent sales – after the trademark holder or one of its authorized retailers has released those goods into the market. Put simply: the first sale doctrine and nominative fair use.

First Sale – Putting aside the use of the Chanel name for a moment and focusing purely on the product resale element, the ability of consumers and companies to freely resell trademark-bearing products is the basic premise of the first sale doctrine. The well-established trademark doctrine provides that the right of a trademark holder to control the distribution of products bearing its trademarks (and bring trademark claims as a result) is exhausted after the first authorized sale of those goods. In other words, an individual/entity can stock and resell genuine trademark-bearing products without the trademark holder’s authorization and without running afoul of trademark law once the trademark holder first sells those goods in a given market.

This rule is subject to some important caveats, at least one of which is at play in Chanel’s case against WGACA and other lawsuits like it. In these cases, counsel for Chanel is looking to chip away at the general rule that trademark-bearing products can be resold without the trademark holder’s authorization and without trademark infringement or other legal ramifications by arguing that at least some of the bags that have been offered up and sold by WGACA were not subject to its inspection and “strict” quality control standards and/or were not found to meet its specifications.

Specifically, Chanel has pointed to 50 bags that were sold by WGACA that came with serial numbers that were not verified by its internal record system, ORLI. As Judge Louis Stanton of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York stated in a March 2022 opinion and order, “Chanel argues that these serial numbers went missing before being assigned to [its] bag[s] and as a result, the ORLI system has no notation that bags with those serial numbers ever passed through the quality control procedure and were authorized for sale.” This is important, as if the bags were not subject to Chanel’s quality control standards and/or Chanel did not approve their original sale and thus, did not release them into the market, the first sale doctrine defense would be of little use to WGACA.

The court seemed skeptical of WGACA’s first sale arguments early on, with Judge Stanton finding (back in 2018) that the first sale doctrine – which “applies only where a ‘purchaser resells a trademarked article under the producer’s trademark, and nothing more’” – likely does not protect WGACA. The basis for this determination: Chanel’s allegations in its amended complaint that WGACA “did much more than laconically resell Chanel-branded products: its presentations were consistent with selling on Chanel’s behalf.”

(The first sale doctrine ended up being one of the issues that is before the jury – albeit indirectly. Refusing to decide at least part of Chanel’s trademark infringement claim on summary judgment in 2022, Judge Stanton held that “the question of whether the bags were actually subjected to [Chanel’s quality control measures]” – and thus, whether Chanel authorized the sale of the bags with these serial numbers in the first place – is one that is “best left for the jury.”)

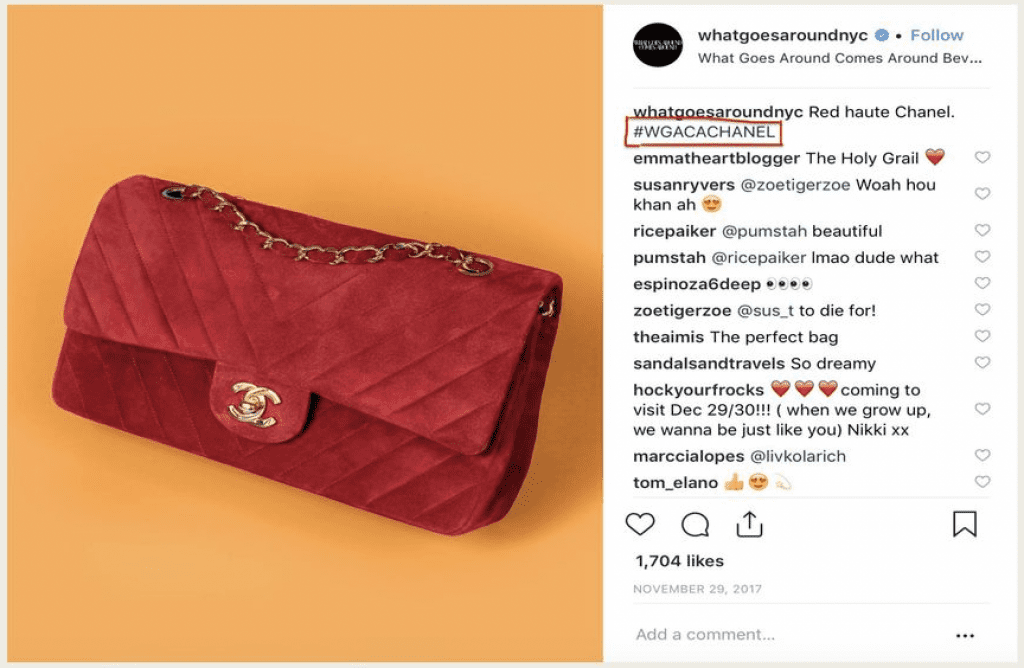

Nominative Fair Use – One of the other critical elements at play in this case stems from WGACA’s use of Chanel’s trademark-protected name (and other branding) in connection with the resale of Chanel products. Chanel has taken the position that regardless of whether WGACA can legally sell the Chanel products at issue, the reseller’s use of Chanel trademarks/branding goes so far as to falsely suggest to consumers that Chanel endorses or is otherwise connected to WGACA’s business. Put another way, WGACA’s use of the Chanel trademark in hashtags, in the language of its authentication guarantees, including statements like “Buy WGACA CHANEL – 100% Authenticity Guaranteed” (more about that here), and in marketing campaigns, among other things, goes beyond the bounds of fair use, according to Chanel.

As such, in addition to a first sale defense, WGACA is relying on nominative fair use as a shield against Chanel’s trademark claims, arguing that its use of the Chanel marks is necessary to identify the products at issue and is limited to identifying/describing the products at issue. Most will not need reminding that nominative fair use allows for the use of another party’s trademark(s) to refer to/identify its products as long as that use does not create a likelihood of confusion among consumers.

The reseller-defendant has asserted that it uses Chanel’s marks exclusively to identify the manufacturer of the products it sells, just as it does for all of the other non-Chanel-branded pre-owned luxury goods it sells.

In an opinion in September 2018, the court rejected WGACA’s fair use argument, determining that its use of the Chanel word mark, on its own, would have been sufficient to identify the pre-owned goods it was selling as originally coming from Chanel. However, the potential problem, according to the court, is that WGACA may have “stepped over the line [and created] a likelihood of confusion” by using Chanel’s trademarks “too prominently or too often, in terms of size, emphasis, or repetition.”

In addition to including Chanel’s word mark in hashtags with its own name (#WGACACHANEL), the court noted in 2022 that Chanel “has evidence [that] … WGACA’s welcome email to customers and Facebook cover photo features the Chanel marks. Its social media … also features Chanel marks and indicia, as do its [in-store] retail displays, and its direct-to-consumer advertisements, one of which featured the Chanel mark more prominently than WGACA’s and in the WGACA stylized font. WGACA also used Chanel marks and indicia in general advertisements for WGACA, and to advertise upcoming sales, despite not advertising any specific Chanel product.”

Taken together, these uses go beyond the identification of specific products, Chanel has maintained in its effort to undermine WGACA’s fair use claims.

THE BIGGER PICTURE: At the most immediate level, this case is about the unauthorized offering of Chanel-branded point-of-sale items, WGACA’s use of Chanel-centric marketing materials, and its sale of Chanel bags with allegedly faulty serial numbers. But beyond the surface, the more important question seems to be: Who other than Chanel can use its name and offer up double-C logo-emblazoned wares?

This is a critical issue in this case (and others like it), as while a number of luxury brands have embraced the secondary market as a way to reach younger consumers and tap into an alternate revenue stream, Chanel has distanced itself from resale – presumably in furtherance of an effort to retain as close control as possible over its offerings and the conditions in which they are sold. Yet, that has not stopped third party resale companies – like WGACA and The RealReal, which is also facing a lawsuit from Chanel – from parlaying demand for pre-owned Chanel offerings and those of other luxury names into potentially big businesses.

The outcome of the case will be impactful both at micro and macro levels. Among other things, it will be telling to see how far third-party resellers (like WGACA) can go in terms of their use of others’ trademarks and broader elements of branding, what they can legally claim from an authentication point of view, etc. It will also be striking to see what defenses work in their favor versus what brands like Chanel can do to chip away at broad applications of the first sale doctrine, for example, in order to retain some of the all-important control that they are desperate to maintain in the market.

The case is Chanel, Inc. v. What Goes Around Comes Around, LLC, et al., 1:18-cv-02253 (SDNY).